IR35 private sector reform

How to reform IR35, keep the Exchequer in funds, and avoid the hassle that comes with the current private and public sector regimes

On May 18th 2018 HMRC published a consultation document proposing to extend the current public sector regime to the private sector. My own view is that this would be disastrous and unworkable.I do nevertheless have sympathy with HMRC’s view that the current private sector rules areunenforceable and the subject of widespread non-compliance, and feel that – with over 80% ofthe take from IR35 being represented by employers’ National Insurance Contributions (‘NICs’) – some radical change is needed.

This paper, which has been submitted to HMRC, suggest a way forward that ought to get the Exchequer 95% of what it seeks without the hassle and the poisonous feelings that have grown up around the public sector reforms.

Is it possible to consider this?

Basically my proposal is similar to the one at paragraph 6.34 in the Consultation Document, by which the client pays the employers’ NICs and the personal service company (‘PSC’) the employees’. This has been ruled out of scope as ‘it would fundamentally change the NICs treatment of those who would otherwise be within the off-payroll working rules’. I confess that I cannot see why it should. It could be done so that the rules apply equally to the client and to the PSC, just with different parties responsible for paying the various parts (the client the employers’ NI and the PSC the employee’s NI and the PAYE).

The client and the PSC could, of course, take different views as to whether IR35 applied, but if they did so one of them would be wrong. However, bearing in mind that virtually all that was being sought would come from the client, there would be very little in it for the PSC and the worker, as I shall show below. This being so, most of them would comply, and the loss to HMRC where they did not would not be serious.

It would be a less bureaucratic alternative to suggest that IR35 did not apply to the PSC in any event, so that all that happened under this rule would be for the employers’ NI to be collected. This would also raise less money, but only marginally less. It would certainly be true under this alternative that there would be differences of treatment as between the client and the PSC, and it may be that prospect that led the authors of the consultation document to suggest that it should be out of scope. Personally, I cannot see any objection to it on that ground and it would make things simpler for small businesses to deal with their tax obligations. However it is not essential to the operation of this proposal.

Point 1 – the end client must be the liable party, not an intermediary.

This seems to me to be both just and essential in any event, irrespective of whether the rest of the proposal is adopted.

It is just because most of the money raised consists of employers’ NICs: in my estimation about 82%. This is, as its common name suggests, an impost on employers and should be paid by employers (in this instance the clients). Putting the responsibility on to intermediaries allows the employers to ignore their responsibilities here. The idea behind this was that the employers should pay the intermediaries enough to cover the employers’ NI, but I know of no-one who thinks that this actually happens in practice – the issue is simply never raised.

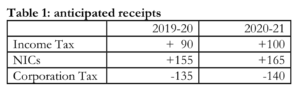

The 82% figure can be gleaned largely from the last Office for Budget Responsibility report, which has the following figures for increased revenue from the new public sector rules. To get there, go to http://obr.uk/data/ and click on Policy measures database, then scroll down to rows 1380 to

1382. I would suggest ignoring the figures for 2017-18 and 2018-19 as it is obvious that it takes time for the full effect of this measure to bring in the full Income Tax receipts. However we see the following for 2019-20 and 2020-21 (in £ millions):

The first point to note here is that the Corporation Tax lost exceeds the Income Tax gained, by quite a substantial margin. As Corporation Tax is a form of income tax paid by companies, and in this case companies owned by people who would be paying Income Tax on the same profits if the companies were not there, it is clear that the measure has not been introduced with this sort of tax in mind. Indeed, as one would expect, the gains come from NICs and easily outweigh the net losses on the income taxes front.

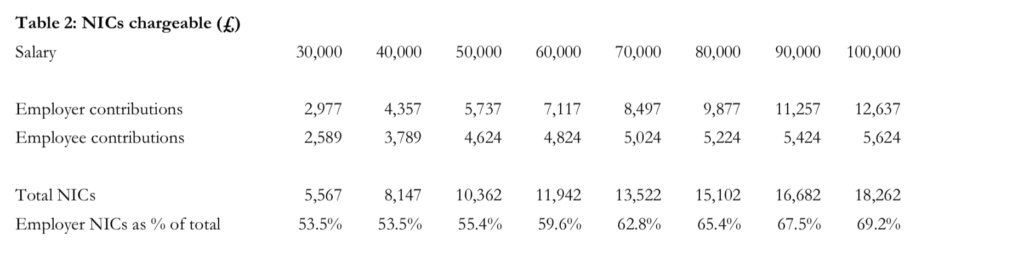

What these figures do not show are the split between employers’ and employees’ NICs, and so I have had to make assumptions here. On the basis that the average deemed salary is £60,000, which would seem to me to be a good working assumption in the absence of any evidence, the proportion is about 60% employers’. As the table below shows, it goes steadily up from 53% on a salary of £30,000 to 69% on a salary of £100,000:

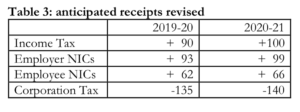

On the assumption then that 60% is correct, this allows us to recalculate table 1 as follows (£ millions):

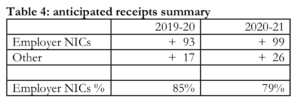

Or, put more simply:

The average is 82%, and in subsequent years it settles down at about this level.

It is essential because otherwise either the employers’ NICs will end up being paid by the worker, which is the source of much unfairness and controversy at the moment, or the intermediaries will resort to avoidance and evasion. The fact is that the intermediaries simply cannot afford to pay the employers’ NICs. At 13.8% on most of the deemed salary, it will be very close to the gross margin (i.e. before overheads) of an agency, and well above the gross margin of an umbrella. If they are to stay in business they need to pass the cost on to someone else. This means that if they cannot charge the client enough to cover it, they reduce the rate paid to the worker. The client obviously has no incentive to pay anything extra, particularly with other agencies being prepared to say that they would take a different view. The only way to make the employers pay is to make them pay directly, not indirectly.

This also avoids the temptation to route payments through non-compliant umbrellas. This I understand to be a major issue in the National Health Service, which has a well-known recruitment problem as it is: it is my understanding that there are some 40-50 umbrella companies, most but not all of them offshore, still paying people though contractor loan schemes, and it is not difficult to see how this happens with these three factors in play:

- NHS trusts (many of which are short of money) refuse to pay any extra to cover the employers’ NI;

- The workers know that they can get higher net pay through umbrellas that give them contractor loans, so they refuse to work for the ones that do not;

- The agencies, unable either to get the NHS trusts or the workers to pay the impost, succumb and contract with these offshore umbrellas. It is likely that in many cases the agency staff would be unaware of what was happening anyway – it is not what they are paid or trained to look out for.

An additional point is that whilst the intermediaries cannot afford to pay this, and the workers see no reason why they should (and often cannot afford it either), many of the clients can absorb the costs without too much trouble. An extra 13.8% on a cost that only amounts to 5% of your total revenue, which will be the case for many enterprises using this sort of contract labour, will put that 5% up to 5.7%, which is unlikely to put the venture at risk, and which they may well be able to recover–atleastinpart–fromtheirclients. Wherethecontractlabourcosts50%oftheirrevenue it is of course another matter, but there will be plenty of cases where this is not so.

If this is a problem in the public sector now, it will be a very much greater one in the private sector if the public sector rules are extended there. The public sector is much smaller and there is more of a compliance culture in it. By contrast, the profit motive in the private sector is likely to come out on top, particularly if businesses can blame someone else for compliance failures.

Added to that, I understand that HMRC are taking action against these non-compliant umbrellas. It obviously remains to be seen how successful this will be, but I do nevertheless have two reasons for being sceptical. Firstly, they are likely to get tripped up when it comes to deciding who the responsible party is. If the worker has a contract of employment with an offshore umbrella, this will be the client (under s. 689 ITEPA), but if not it will be the agency (under s. 44). HMRC will not find it easy to establish the truth as it will have no powers of inquiry vis-à-visthe umbrella, and any attempt to find out from the other party to the contract (the worker) will certainly be time-consuming and probably fruitless. They will therefore be obliged to assume that it is not and challenge the agency to prove otherwise. As most contracts between umbrellas and workers are contracts of employment, their chances of being wrong-footed by an agency that does find out the truth are quite high. With non-compliant onshore umbrellas it will usually be the umbrella that is liable, but there will invariably be no money in it. I suspect that this is going in itself to need legislation to deal with.

It is also worth pointing out that, if found to be on the wrong side of the law, clients are much more likely to pay up than umbrellas or agencies. Intermediaries basically exist to pay out what they get in and rarely have much in the way of reserves (umbrellas in particular). They are more likely to shift their businesses into another company and start again there, leaving HMRC to salvage what little it can from the wreckage.

Thus it can I hope be seen that making the client liable ought to bring three benefits:

- It will prevent the practice of making the workers suffer the employers’ NI;

- It will forestall evasion through umbrellas offering contractor loans;

- HMRC are more likely to recover what they are owed when the law is transgressed.

Point 2 – liability for employee taxes and NICs should remain with the PSC

This means that the PSC would have to operate PAYE on all its receipts under IR35 contracts and pay employee NICs, but not employer NICs as these will have been dealt with already. This has these advantages:

- It prevents arguments. One of the side-effects of the new public sector rules is that there are two industries where relationships between the clients and their workers have become absolutely poisonous, these being broadcasting and the health service. It is no accident that these are industries where staff costs are high as a proportion of revenue and the clients cannot easily afford to pay the extra. However the workers are not locked in a struggle with HMRC about this: they are locked in a struggle with their clients, which is tying up management time to unproductive ends and cannot be good for business in the long run. If the PSCs were left to sort out the employee taxes themselves as well as the clients being left to sort out the employers’, there would be no reason for this and it should all disappear, and with it a great deal of pressure on HMRC who I know are also spending an inordinate amount of time dealing with the problems.

- Administration would be much easier. The PAYE system is simply not designed to collect tax off payments not made to workers directly, and this explains a good deal of the awkwardness that surrounds the current public sector regime. Software would be required that recognised when employers’ contributions were not payable, but this is hardly novel – we have the Employment Allowance already.

- Big business would also find the software much easier. Frequently large companies’ systems are integrated and the introduction of something as complicated as the public sector rules will have knock-on effects. In this instance one has to identify people who are like employees, and so go through the payroll, but are not actually employees, and so do not appear as such in management statistics. They can also be paid VAT, which employees cannot, but on an amount that on the face of it looks incorrect. Leaving big business simply to pay an NI charge on certain contracts, which its software could identify quite easily once the contracts themselves had been identified, would be a great deal simpler. I would hazard a guess that this might enable the reform to be introduced a full year earlier.

- PAYE tax coding would suit the worker and avoid the need for extra tax to be paid through SA returns, or for refunds to be made. Currently unless the fee payer gets a P45 it is supposed to use the BR code, which will lead to the wrong amount of tax being paid – generally an underpayment.

Additional paperwork

Any additional paperwork will be unwelcome, but one piece is essential here which I believe will be simple to operate and far easier to understand than the current public sector system. The client will need to give a certificate to the next in the chain to say that IR35 is being operated, and the next in the chain will be required to issue a certificate to that effect to the next, and so on until one gets to the PSC. This will have two effects:

- It will authorise the PSC not to pay employer’s NI contributions on any salary up to the amount on the certificate; and

- It will at the same time put the PSC on notice that the client is applying IR35. The PSC will therefore need to have good grounds not to do the same. HMRC would be able to have regard to the fact that the client had issued a certificate when investigating the PSC, and I would expect the Tax Tribunal to take it into account as well in any subsequent action in that forum.

There would need to be penalties for failure to pass these certificates on, and it would help if there were incentives to do so as well. As between the client and the agency, one possible way of doing this would be to allow the agency to get a rebate for employer’s NICs paid on sums that exceed the amount paid to the PSC. For example, if the client pays the agency £100 and the agency pays the PSC £85, then the client will have paid £13.80 in employers’ NICs on a deemed salary of £85, a rate of 16.2%. If the agency could claim back the NICs on the differential (£2.07 in this instance), this would give it the incentive to get the certificate from the client, as well as providing an automatic mechanism for getting the employer NICs paid at the right rate on the right amount. I would also expect the market to work in this instance, so that agency margins were reduced to compensate.

As between the agency and the PSC, it would probably be necessary for the agency to get confirmation from the PSC that it has received the certificate and to be able to refuse to pay until it does so.

Possible objections

Objection no. 1 – the client pays NICs on a higher sum than the deemed salary paid to the worker.

This is because of the agency’s margin, as noted in the previous section. My preferred solution would be the one suggested in that section, but an alternative would be to charge NICs at a lower rate where IR35 is in play. If one works on an average agency margin of 14%, the rate would be 11.9% instead of 13.8%.

Objection no. 2 – the client has to work out which contracts are paid through PSCs and which are not.

There may be other off-payroll workers paid through umbrellas or directly by the agency. The short answer is that clients have to do this now in public sector cases – the only difference will be that they will have to pay the employers’ NI themselves where IR35 applies, but will have to give the agencies enough money for parties down the chain to pay it where the agency rules apply or where an umbrella has a contract of employment with the worker.

If this is an issue (and I do not see why it should be – agencies are quite adept now at collating the requisite information about how people are paid further down the chain), it might be worth considering extending this regime to agency worker cases as well. This would resolve a number of problems in the agency sector, which has many of the issues described above too.

It would in turn however necessitate distinguishing cases where the SDC test applies (for agency workers) from those where the normal employment status test does (in PSC cases). The result would generally be the same anyway, but again, if this is considered an issue, it might be worth while standardising the entire intermediary sector around the SDC test, which would certainly be simpler to operate.

Objection 3: the PSC might take a different view.

As noted above, it would be doing so on notice that it was taking a different view, and so much more aware of the risk that it was running than it is now, where many PSCs do not perceive any risk at all. If the certificate were to include a statement that that the PSC was recommended to show it to the company’s accountants or tax advisers – a statement that could be made mandatory – most of their accountants would become aware of the issue too: something that is conspicuously lacking at the moment. All this would encourage compliance.

However I suggest that the most likely factor to encourage compliance would simply be that it would not be all that costly to comply. It would also be administratively easier, in that payment of tax would all be done through PAYE not long after the money is received, and not through and combination of Corporation Tax and Income Tax a long time after. Although it would mean paying tax earlier, many PSC owners would prefer that if it means that they do not have to keep track of large liabilities looming many months ahead.

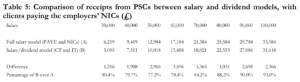

The table below shows the difference in taxes paid by the PSC and the individual as between a full salary model and a salary/dividend model.

Using the £60,000 average once again, this would mean that with a compliant client and a non- compliant PSC, HMRC would receive:

- All of the employer’s NICs (82% of the total due)

- 78% of the 18% due from the PSC (14% of the total due).

Thus even if all PSCs failed to comply, HMRC would still receive 96% of the sums due to them.

It would be untrue to say that nobody would consider these differences to be too small to be worth forgoing the money, but many would think that, when they weighed in factors such as ease of administration and the risk of being found non-compliant, they would prefer to use the PAYE model.

Objection 4: this does not deal with the problem of income splitting.

Income splitting is a set-up whereby the PSC is not wholly owned by the worker, but some shares are also owned by his spouse. This enables him to divert dividends (but not salary) to that spouse and so double up on the personal allowance, the dividend allowance and the basic rate band. This was found to be legitimate by the Supreme Court in Jones v Garnett [2007] STC 1536.

I do not see this as a major problem. This was widely used in the days when wives did not do paid work, but that is comparatively rare nowadays. It is only of any real use where there is a serious disparity of earnings as between the two, and very rarely of any use except where the lower earning spouse earns substantially less than the top of the basic rate band. Also it is my experience that, even where it might be of benefit, people are reluctant to ‘give’ their earnings to their spouses in this way, for reasons of retaining control over those earnings.

Objection 5: this does not take account of people stacking up their profits in their PSCs and not distributing them.

It is possible to avoid Income Tax altogether (paying only Corporation Tax) by drawing from one’s PSC only sufficient to pay one’s living expenses, and saving up the rest in the company. The plan would be to liquidate the company when the worker has no further use for it and pay Capital Gains Tax on the final distribution, claiming Entrepreneurs’ Relief and so paying CGT at 10%. Otherwise only Corporation Tax is paid on the profits.

Despite the propensity of some parts of the press to draw attention to this possibility, in my experience very few PSCs do this: most people need the money to live on. I do not therefore see this as a major problem.

Objection 6: this does not deal with the problem of PSCs that get incorporated and then never file anything

Under this type of evasion the PSC receives all the money from the contract, pays it out to the worker, and never files any further paperwork with either HMRC or Companies House. The result is that the company gets struck off the register after little more than a year, and well before HMRC realise that there is anything that needs investigating there. If the worker still has any use for a company, he will set up another one and repeat the process.

This is not particularly an IR35 problem, and in my experience the only sector where I have seen it in operation at a serious level is construction. Paradoxically, not much money is likely to be lost to HMRC in this sector because of the Construction Industry Scheme, which is a good antidote to this. It is nonetheless very difficult for someone without access to HMRC’s figures to estimate how serious this is. It is, though, a flagrant example of evasion of tax, and will not appeal to people who are prepared to indulge in avoidance but draw the line at evasion. If it is perceived to be a serious problem, the solution is that suggested and discarded on paragraph 6.36 of the consultation document (a withholding tax similar to that operating in the construction industry). This would be very bureaucratic and is not recommended unless substantial sums outside the construction sector are at stake.

Conclusion

In summary, I recommend this model for serious consideration. The first part – placing responsibility on to the client rather than intermediaries – seems to me to be essential in order to make the private sector roll-out leak-proof. The second part – leaving responsibility for the employee taxes with the PSC – would be much easier to operate, would reduce the lead time for introducing it, and would remove a great deal of the political heat from the scene in exchange for leaving the Exchequer with a very small, and certainly manageable, loss of tax.